The data

A nationally representative survey commissioned by the Institute for the Impact of Faith in Life (IIFL) and carried out by British Polling Council (BPC) member TechneUK between the 29th of September and the 8th of October 2023, provided a snapshot of the strength of belonging that people in the UK feel in the following ‘spheres’ of life: family, friends, work, and neighbourhood.

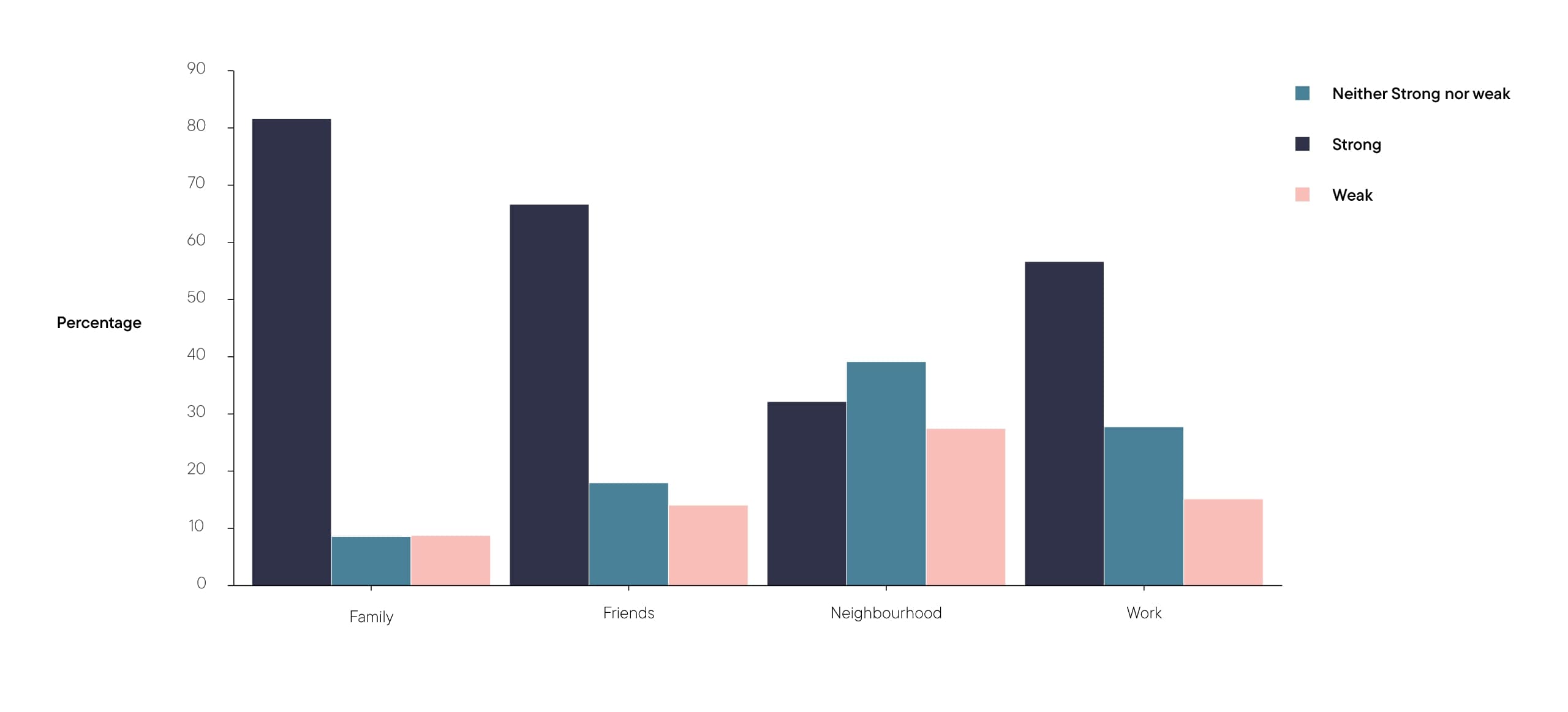

Figure 1 shows that among the UK respondents polled, more than four in five (81.5%) reported a strong sense of belonging within their family (with 8.6% saying it is weak). This means around one in five respondents did not report a strong sense of belonging within their family.

Two thirds of the UK respondents (66.5%) stated that their sense of belonging within their friendship network is strong. Despite the ability to self-select and freedom to shape friendship groups, 13.9% say that their sense of belonging in this sphere of life is weak.

The majority of respondents (56.5%) say that their sense of belonging at work (and wider employment network) is strong. While more than a quarter said it is neither strong nor weak (27.6%), 15% said that it is weak.

The most underwhelming figures are for people’s sense of belonging within their neighbourhood. Under one in three UK respondents (32%) said it was strong in this sphere of life. One than one in four (27.3%) reported that their sense of belonging within their own neighbourhood was weak.

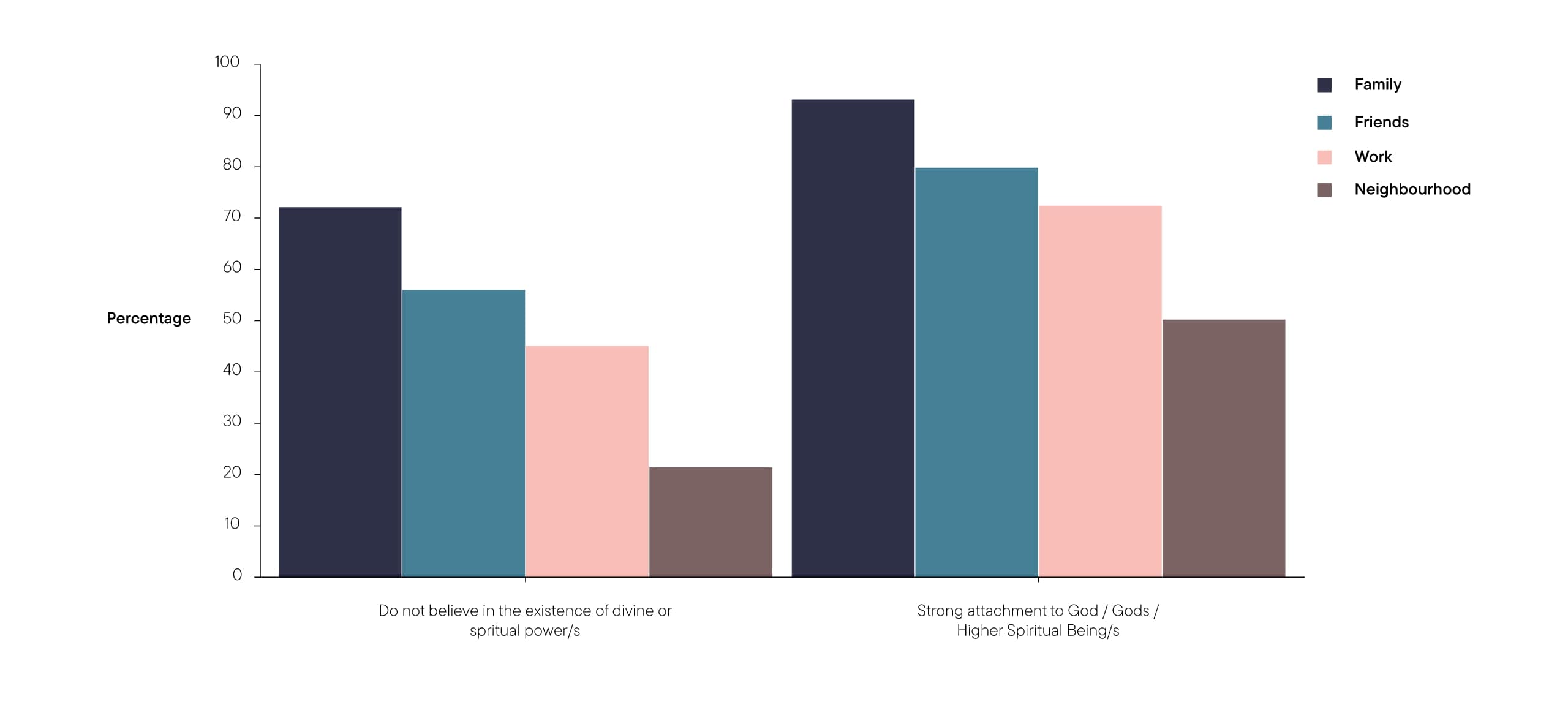

Figure 2 explores the relationship between strength of religiosity (and spirituality) and reporting a strong sense of belonging across the four ‘life spheres’ – family, friends, work, and neighbourhood.

There is a consistent and notable relationship between high levels of religiosity/spirituality and being more likely to report a strong sense of belonging (across all four life spheres).

Among those who report a strong attachment to God/Gods/Higher Spiritual Beings, there are high levels of a “strong sense of belonging” within one’s family (93%), friendship network (79.7%), working life (72.3%), and local neighbourhood (50.1%) are the following. For those who do not believe in the existence of any divine or spiritual power/s, this drops to 72%, 55.9%, 45%, and 21.3% respectively.

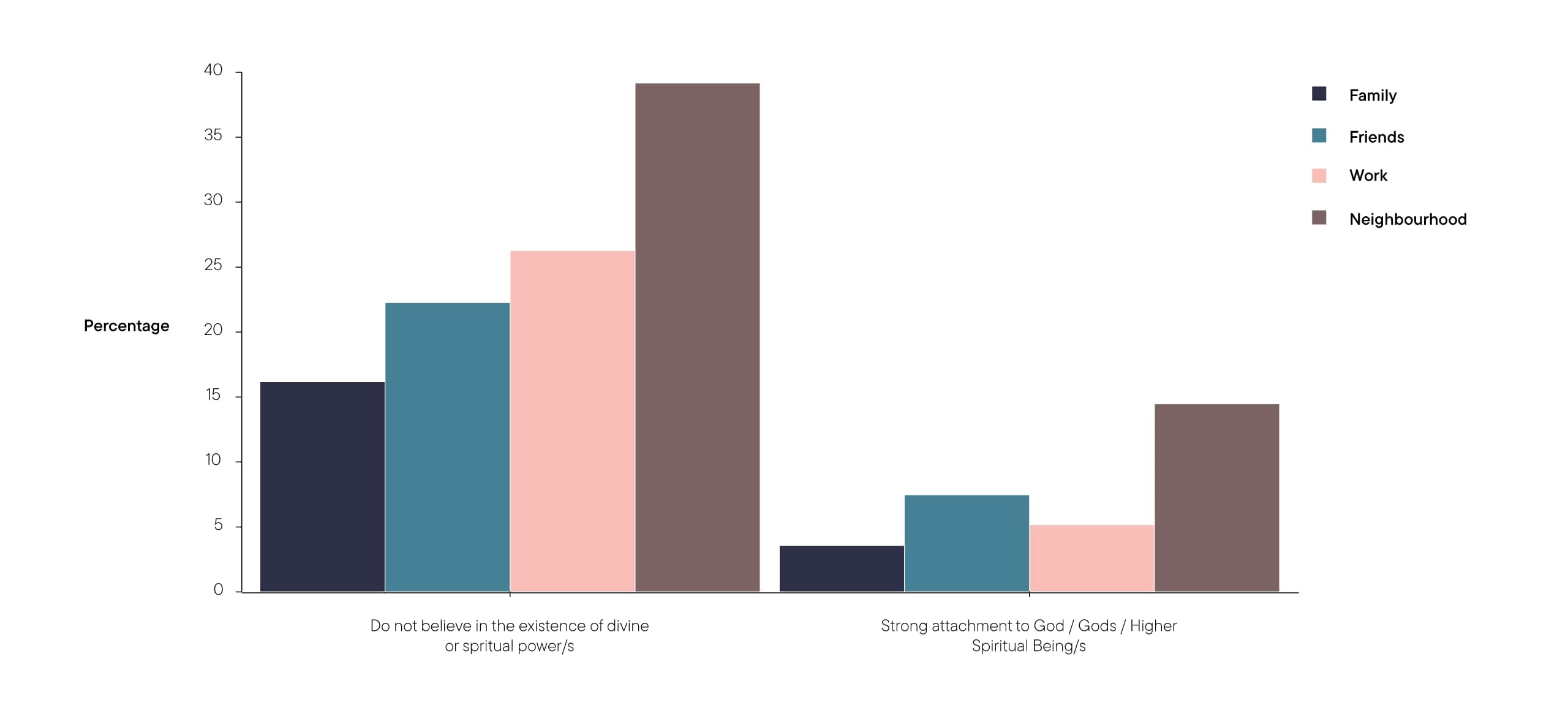

Figure 3 presents an overview of the relationship between religiosity (and spirituality) and reporting a weak sense of belonging across the four life spheres (family, friends, work, and neighbourhood).

There is a consistent and notable relationship between atheism/outright non-belief of divine/spiritual power/s and being more likely to report a weak sense of belonging (across all four life spheres).

Among those who report a strong attachment to God/Gods/Higher Spiritual Beings, there are low levels of “a weak sense of belonging” within one’s family (3.5%), friendship network (7.4%), working life (5.1%), and local neighbourhood (14.4%). For those who do not believe in the existence of any divine or spiritual power/s, this rises to 16.1%, 22.2%, 26.2%, and 39.1% respectively.

Concluding thoughts

The data suggests that there is a significant association between stronger forms of religiosity (and spirituality) and having a strong sense of belonging across different spheres of life.

This could be down to several factors. It may well be the case that a robust religious affiliation can shape one’s approach to family, friendship group, their choice of workplace and indeed residential selection – with overlapping forms of ‘ingroup trust’ being at the heart of a strong sense of belonging. Regularly attending services at a place of worship can be a vital source of social capital – building friendships, opening economic opportunities, and ultimately deepening one’s own belonging in their local area.

However, connection to the divine and spiritual may inspire a sense of duty and respect towards others – helping to develop positive ties with friends, work colleagues and neighbours. These non-familial bonds can transcend a specific religious affiliation – helping to form bonds outside of the ‘ingroup’. Indeed, various forms of faith-based civic activity are not necessarily restricted to one’s own religious group – such as supporting the activities of an interfaith charity.

In a society which has become increasingly secularised, atomised, and individualistic, more work should be done to understand how faith and spirituality undergirds multi-generational cohesion within traditional-minded families and communities.